In the northern hemisphere, August has become the ‘go away’ month. Everything slows down and you can’t be sure that you’ll get a response. In those circumstances, we are risking affront by suggesting the need for a radical and fundamental review of cash and the cash cycle. Replies welcome!

What our industry and the central banks are often failing to do is to step back and think laterally. How can we marry up digital and analogue, what can’t digital replace, are there new business models etc?

At G+D’s Currency Technology Symposium in July, the story was told of how it invented the eSIM card with which we are now so familiar. Producing SIM cards was not profitable and G+D rethought what they did and how it could be done. Across every industry, every process, a combination of factors, particularly the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), means that change is upon us. In our own industry, cash, we are seeing major changes.

The story goes that an Anglo-Saxon King, Canute, was constantly told by his courtiers that he was exceptional with amazing powers. When he ordered the tide not to come in, he found his courtiers were wrong and he got his feet wet. As we strive to sustain cash by pointing out its undoubted strengths, making the cash cycle ever more efficient and seeking legislation to mandate its acceptance, are we missing a trick blinded by our cash beliefs?

A recent blog pointed out that bank technology failures are becoming more common 1. For example, in the UK, according to data from the House of Commons Treasury Select Committee, Barclays Bank suffered 33 system failures between January 2023 and February 2025. Over the same period, HSBC and Santander were both hit by 32 outages.

A recent survey by 10x Banking found that more than half of banks’ decision makers believe their data silos and production bottlenecks are key barriers to embracing new technologies like artificial intelligence 2.

43% of US banks core systems are based on COBOL mainframe systems, with their 60-year old programming language 3. This can only be because of a fear of risk and of failure. Sandboxes are fine, but changing core systems is hard. A balance is needed between change that equals risk, and change that equals innovation and differentiation; this is the constant battle within all institutions, but particularly central banks and the cash industry.

Faced with a technology-driven change, how have other industries responded? What can we learn from their experience?

There are many other examples, but across them all organisations have created new business models and/or used new technologies to drive convenience and lower costs, focusing on what people need, being about people and the things people like.

While there are those who prefer books, bikes, cameras with films, records/ tapes, arguing that analogue is richer than digital, those are increasingly niche products. Digital is not always best – for example, until ‘range anxiety’ is fixed for lorries and cars, it looks like the internal combustion engine is not being defeated by electric vehicles.

But can we do for cash what Netflix or podcasts have done for TV and news?

This article is arguing for radical transformation across all aspects of cash – from production to consumer usage to the cash cycle, across central banks, suppliers and cash cycle stakeholders – in how we create, deliver, and capture value.

A recent PwC article considered this whole topic 4. 52% of the companies that were listed on the Fortune 500 in 2003 have since gone bankrupt, been acquired, or otherwise ceased to exist. 45% of respondents in PwC’s most recent Global CEO Survey said their company won’t be viable in ten years if it sticks to its current path.

PwC argues that we should not see this in terms of ‘doom and gloom’ because every problem, every risk, contains the seed of significant rewards if you can identify and seize the opportunities they present.

This isn’t about the usual responses to disruption such as slashing costs or transforming operating models, even if doing these will almost certainly be necessary. To change we will have to be comfortable with challenging long-held assumptions about how industry stakeholders make money, especially since these assumptions are what brought success in the first place for many decades.

There is also evidence that the currency industry is doing one of PwC’s key recommendations, collaborating to compete in order to gain benefits – including access to new customers and markets, privileged insights such as data on customers’ needs, and complementary skills and capabilities. It argues that ecosystems will be the primary mode of competition.

Delivering day-to-day dependability again and again means you have to be organised. In ‘normal’ times, this delivers stability and continuity. When it’s time for a change, moving away from your organised model becomes a problem. PwC recommends, therefore, that housing a new business model separate from the rest of the company is one way to overcome the resistance to change.

PwC lists the following sources of inertia from today’s steady state which are frequently experienced:

When making a change, reallocating capital and resources is always hard. In PwC’s CEO Survey, nearly two-thirds of respondents reported

reallocating 20% or less of resources (including people) from year to year, and almost 30% of CEOs cited resource reallocation of 10% or less. That is despite the fact that higher levels of annual reallocation in the survey were associated with both greater levels of reinvention and higher profit margins.

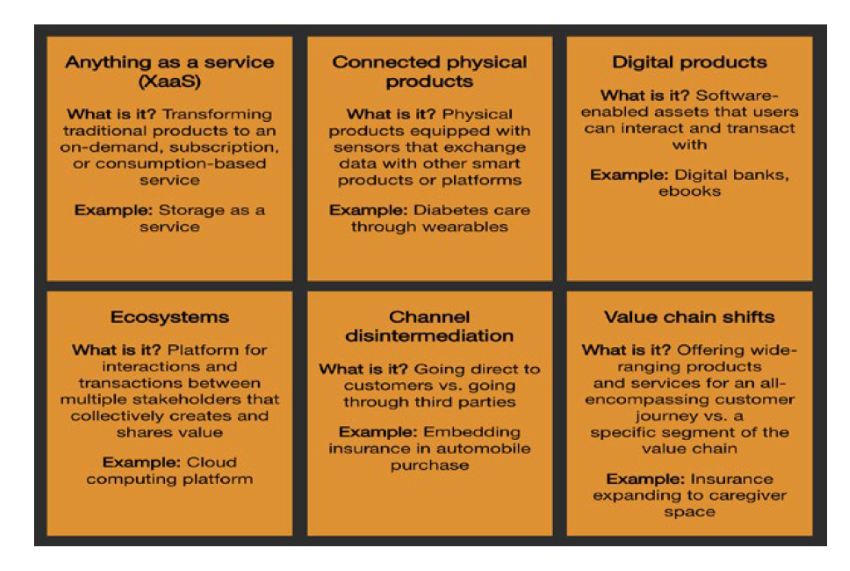

The graphic below shows six examples of winning business model designs that companies use to reinvent themselves. At first glance not all are applicable. However, it is an interesting exercise to challenge yourself about whether they could be useful for cash and the cash cycle. Why not ‘banknotes as a service’ (lease them don’t buy them)?

Connected physical products is an obvious opportunity which links closely to ecosystems. Again, channel disintermediation is already happening to a small extent when banknotes are delivered in the post etc.

It would be easy to read this as being about the private sector, but I would argue it applies just as much to central banks and treasury departments.

Why not step back and see if you can find people who can think radically about fundamental change? The need is visible. The prize is enormous both for society and for those in the cash business.

2 - ‘Core Technology Holding Us Back’ say 55% of banks – new 10x Banking research reveals

3 - Why COBOL Still Dominates Banking. Will the last COBOL guy turn the banks’ lights out?