COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on the global poor. It has also strongly impacted the lives of many women, and, as a consequence, children, the world over. In addition, the pandemic implicitly helped autocratic regimes, or, as Freedom House put it in its post-pandemic report on the state of freedom in the world, ‘Democracy under Lockdown’. For everyone thus affected by COVID-19, cash is often a lifeline, a means of support, of escape and maintaining personal freedom, of independence and of securing livelihoods.

Looking at global developments, facts and figure, cash matters – now more than ever.

In the media coverage on cash in the past two years, the narrative was more or less unequivocal: cash is about to die, and COVID has been the final nail in the coffin.

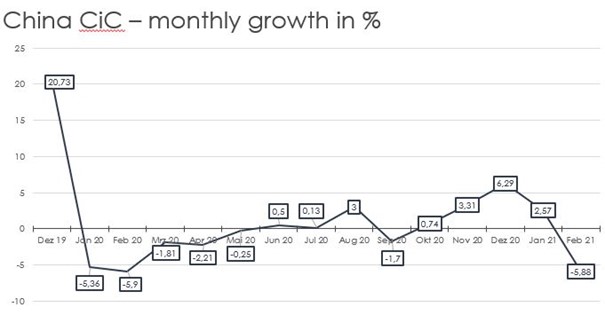

Looking at the hard figures in 2020, the opposite is true: cash demand has soared in almost all countries across the globe, with a spike in the first two months when the pandemic hit. Crises always show the population’s trust in cash, even in China where the government is nudging people toward non-cash payments.

There are two reasons for this discrepancy called the cash paradox.

The first is that media coverage on cash is negligible compared to the coverage on mobile/digital ways of paying, since non-cash payment providers have huge marketing budgets at their disposal.

The second reason is, that cash usage has indeed been declining in many parts of the world while demand for cash as a storage of value has not. This phenomenon is not COVID-related but has indeed been accelerated by it; as the European Central Bank noted in February this year, ‘in recent years, the demand for euro banknotes has constantly increased while the use of banknotes for retail transactions seems to have decreased.’

The question is, whether cash usage will recover or whether cash in circulation will eventually follow the downward trend in cash usage, especially with an increasing choice of digital payments at people’s fingertips and the issuance of CBDC imminent or already in roll-out, as for example in China or the Bahamas.

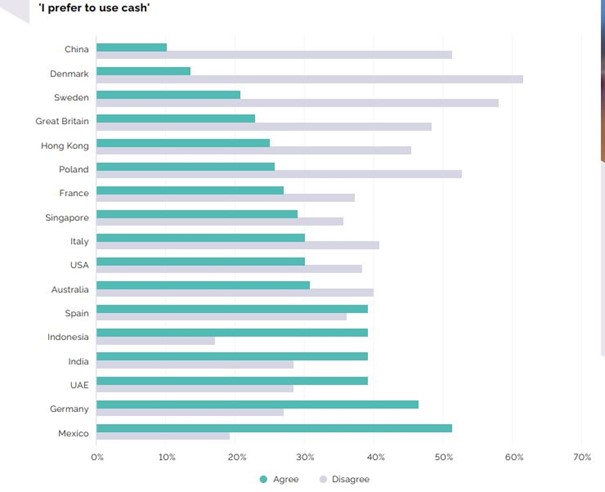

A YouGov poll from February this year shows preferences for cash in decline:

Figures from Europe appear to confirm the trend. In its annual payments report in January, the Bundesbank noted that, compared to 2019, cash transactions were down 13% in 2020 to 61% of all payment transactions. And in Belgium, the Financial Services Industry Federation and Brussels’ Free University Belgium reported a decline in cash transactions by 39% in 2020, with the elderly (65-74) using cash for only 9% of transactions.

However, broadening the perspective into a global one and looking beyond the industry, the picture is quite different. Cash has become even more relevant for a variety of reasons. The drivers for cash usage are (broadly speaking) economic growth, which is usually proxied with nominal gross domestic product GDP; access, availability and acceptance of cash; crises (demand for cash as a storage of value rises); high-tech versus agriculture; state intervention; entrenched habits; demography and the so-called digital divide, including the unbanked and underbanked.

COVID-19 has had a huge impact on some of these drivers, not only but especially in the Global South, in the Latin Americas, India and Africa.

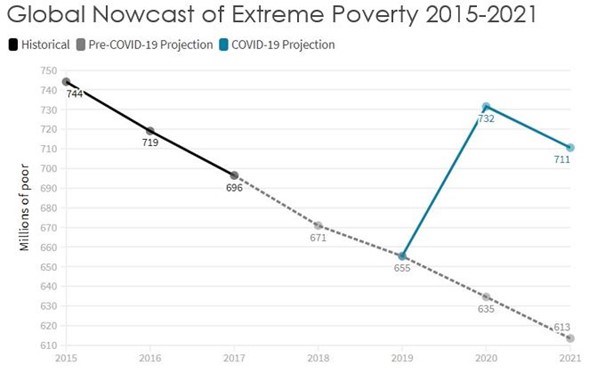

COVID-19 hit the poorest the hardest, not only in terms of infection (cramped quarters, insufficient access to medical supplies and help) but also in terms of loss of livelihood. Roughly estimated, almost 10% of the world population, 717 million people, live in extreme poverty, ie. on $1.90 or less a day as defined by the World Bank. In 1990, this figure was over one third of the population; since then, more than 1.2 billion people have risen out of extreme poverty.

The pandemic meant a harsh setback in the global the fight against poverty as, for the first time in 20 years, poverty is likely to significantly increase, by '97 million more people being in poverty in 2020’, which ‘represents a historically unprecedented increase in global poverty'.

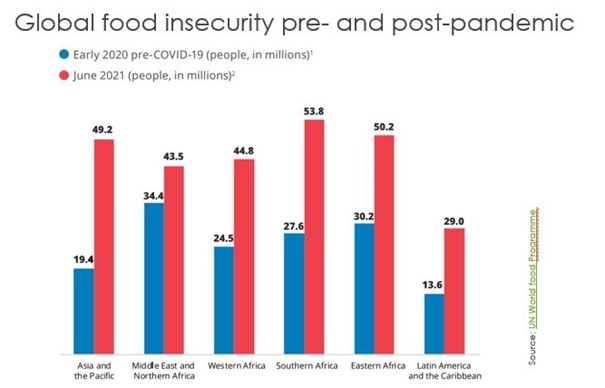

The rise in global poverty due to COVID-19 is closely linked to an increase in global food insecurity. About 2.5 billion people live in moderate and severe food insecurity, out of which up to 270.5 million people are estimated to be acutely food insecure or at high risk in 2021 across 80 countries. Up to 120.7 million additional people are facing food insecurity today compared to before the pandemic, an unprecedented and alarming increase of 81%.

Many humanitarian aid organizations have begun to use cash in their aid programs. The UNHCR, for example, ‘uses cash-based interventions to provide protection, assistance and services to the most vulnerable.’

The UN World Food Programme (WFP) ‘uses cash transfers to empower people with choice to address their essential need in local markets while also helping to boost these markets’. Due to COVID-19, the WFP ‘continues to scale up cash-based transfers, having transferred US$ 710 million across 62 country offices, and is supporting 40 governments worldwide in designing, delivering, and assuring their cash-based transfer programmes.’

For the vast majority of the global poor, cash is the only form of payment available to them. It is a means for survival since cash usage does not involve fees, and no registration is needed to obtain, spend or accept it. It also leaves people their dignity, as cash can be spent without restriction on any product and in any location of their choosing.

Global statistics on the unbanked and on poverty also show a high correlation: 75% of all unbanked people are poor. In its latest ‘Financial Inclusion Survey 2019’, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) for example records a general increase in account ownership but has to concede that ‘[l]ack of enough money remains the topmost reason for not having an account, as reported by almost half (45%) of the unbanked’. This is followed by perceived lack of need for an account (27%) and lack of documentary requirements (26%). The number of unbanked Filipino adults stood at 51.2 million in 2019, or 71% of the total adult population.

According to the Global Findex Database 2017, every third adult globally is unbanked, ~1.7 billion people. More than 20% of adults globally receive wages or government transfers in cash, and many people in developing countries pay all their bills in cash.

For the unbanked, access to financial services comes at an extra cost.

Claiming that digitalisation or crypto assets are the only way for financial inclusion is either wishful thinking or an implicit way of exploiting the poor even further.

In most cases, access to the formal banking system – opening and managing bank accounts, online banking, bank-issued card and mobile payments – requires a digital infrastructure and digital literacy. Often fees are involved when opening an account and using bank-issued cards or apps.

However, it is not only complex application or handling processes that prevent underserved or unbanked populations who may not have formal identity documents from financial inclusion.

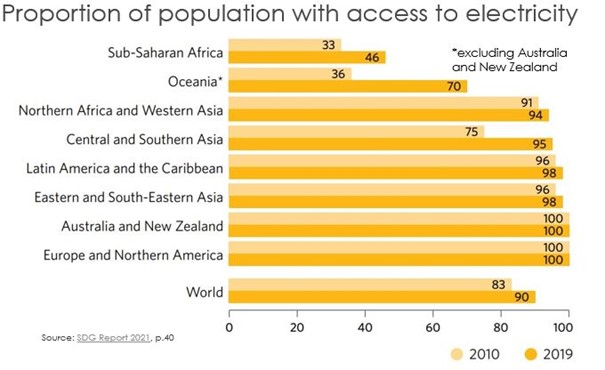

With almost 760 million people globally without access to electricity, three quarters of them in sub-Saharan Africa, integration into the formal banking system is probably the least of their worries, let alone easily achievable.

The UN states in its SDG Report 2021: ‘The COVID-19 pandemic could reverse progress in some countries. In Africa, the number of people without electricity increased in 2020 after declining over the previous six years. In developing countries in Africa and Asia, basic electricity services are now unaffordable for more than 25 million people who had previously gained access, due to population growth and increasing levels of poverty. An additional 85 million people, mainly in developing countries in Asia, may be forced to scale back to basic electricity access because of an inability to pay for an extended bundle of services.’

It is no big surprise then, that, at the beginning of 2021, the World Bank stated: ‘Half of the world’s population is still without internet access, with the vast majority concentrated in developing countries.’

Cash is a societal equaliser. It does not discriminate between rich or poor, between banked and unbanked. It is available to all, regardless of social status, creditworthiness, age, race, gender, nationality etc. Everyone can use cash; the same note connects a street hawker to an investment banker.

Cash is a public good. It is the only form of money that citizens can use independently of its issuer. As Canadian economist Pierre Lemieux put it: ‘It is an intriguing fact that the availability of government currency provides protection against government intrusion itself.’ Protection of privacy and protection of data are a subset of the characteristics of cash as a building block for personal freedom and independence.

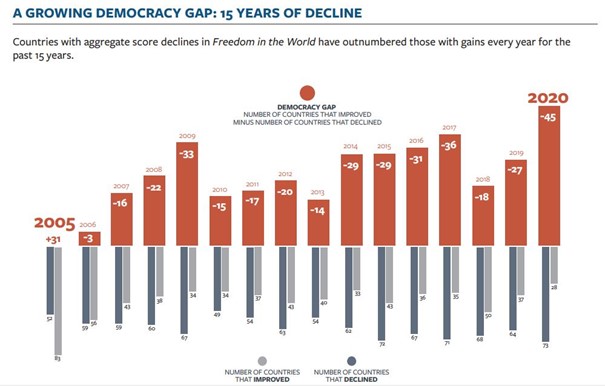

In its 2021 report, ‘Democracy under Siege’, Freedom House notes: ‘As a lethal pandemic […] ravaged the world in 2020, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses […]. Incumbent leaders increasingly used force to crush opponents and settle scores, sometimes in the name of public health, while beleaguered activists— lacking effective international support—faced heavy jail sentences, torture, or murder in many settings.’ The chart clearly shows the huge negative impact of COVID-19 on freedom.

Whenever people are fighting for freedom under oppressive regimes, cash is one means to mitigate repression. Dostoyevsky’s relatives knew this when they hid cash in the bible they gave him after he had been sentenced to prison.

Hong Kong students used cash, many of them for the first time, when rallying for their protests, as the Bitcoinist reported: ‘Hong Kong is waking up to the benefits of financial privacy using cash, reports claim, as protesters seek to hide their movements and identity. According to various reports surfacing on social media this week, participants in the ongoing rallies against the Hong Kong government are choosing to abandon payment methods which could track them.’

And, in a different context, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) published a feature titled Say No to the ‘Cashless Future’ – and to cashless stores in 2019, stating that ‘the rise of cashless establishments is happening amid continuing hype over the supposed dawn of a ‘cashless future’ and agitation by some very powerful interests that would love to see cash disappear.’

Cash helps people to defend their privacy and to shield from prying eyes with no business to interfere in their lives.

There has been abundant media coverage about the negative impact of COVID-19 on women, in almost all countries and all aspects of their lives. As the UN put it: ‘[W]omen and girls face disproportionate impacts with far reaching consequences that are only further amplified in contexts of fragility, conflict, and emergencies. Hard-fought gains for women’s rights are also under threat.’

In the developing world, the effect was particularly devastating. The ILO estimates global unemployment to rise between 5.3 million (‘low’ scenario) and 24.7 million (‘high’ scenario) from a base level of 188 million in 2019 as a result of COVID-19’s impact on global GDP growth.

UN Women survey results from Asia and the Pacific show that women are losing their livelihoods faster than men and have fewer alternatives to generate income. In addition, due to the confinements imposed by Covid-19, violence against women has increased. They often also have less access to basic sanitary and health measures and are required to do more unpaid work such as caring or cleaning.

Women need emergency funds now more than ever. And in most of the developing world, they need them in cash. They don’t need a husband’s permission to save in cash, they don’t have to be able to manage a bank account, they don’t need to visit a bank.

In India for example, ‘millions of women […] keep bundles of cash stashed away in hidden biscuit tins or tupperware, under sinks, or at the back of wardrobes, […] hoping to pitch in for their children’s weddings or education, or save for old age’, noted The Guardian in 2016.

But it’s not only women in developing countries who have been hit hard by COVID-19. McKinsey reported in its 2021 study ‘Covid-19’s impact on women’s employment’ that ‘[w]omen in France, Germany, and Spain will have an increased need for pandemic-induced job transitions at rates 3.9 times higher than men’, meaning that women lose their jobs much faster than men.

Correspondingly, in March this year, The Independent published a feature ‘Women need emergency savings now more than ever’, leading with: ‘Extra funds aren’t just for rainy days or broken boilers. They are about the freedom to leave bad situations. This pandemic has shone a brutal light on women’s financial inequality at the same time as it deepened those inequalities.’

Many women in the developed world use credit cards or bank accounts of their own as their emergency fund, in order to be able to ‘make choices about situations they are in’. But even in industrialised countries, cash is often the last resort for everyone defending their personal freedom, independence and liberty.

Only cash prevents total control – regardless of the context, be it private, governmental or institutional.